Reading Processes in Literary Translation. How Specific are they?

Dolores Aicega[1]*

Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación

Universidad Nacional de La Plata

Argentina

Resumen

Este trabajo se propone explorar la lectura de textos literarios cuando esta forma parte del proceso de traducción. En términos generales, nuestra investigación busca contribuir a la descripción de los procesos de lectura que se dan en la traducción literaria. Para ello, recurrimos al modelo de comprensión de textos de van Dijk y Kintsch (van Dijk, 1978, 1980, 2014; van Dijk & Kintsch, 1983) y mostramos que resulta insuficiente para abarcar los aspectos más específicos de la lectura de textos literarios para la traducción. Luego, analizamos algunas contribuciones del campo de los estudios de traducción, particularmente el concepto de mapa del texto fuente desarrollado por James Holmes ([1978]1988) y la noción de competencia traductora de Hurtado Albir y el grupo PACTE (Hurtado Albir, 1996, 2001; PACTE, 2003). Finalmente, presentamos una propuesta para un modelo integrado de los procesos de lectura en la traducción literaria que articula las ideas de Holmes con el modelo de van Dijk y Kintsch utilizando el concepto de competencia traductora como concepto-puente.

Palabras clave: traducción literaria, procesos de lectura, comprensión de textos en traducción.

Abstract

This paper aims to explore the processes involved in reading literary texts as part of the translation process. In general terms, our research seeks to contribute to the description of the reading processes which occur in literary translation. We begin by showing that van Dijk and Kintsch’s model of text comprehension (van Dijk, 1978, 1980, 2014; van Dijk & Kintsch, 1983) is not enough to account for the specific nature of these processes. Then we analyse some contributions from the field of translation studies, particularly James Holmes’s ([1978]1988) concept of map of the source text and Hurtado Albir and PACTE’s notion of translation competence (Hurtado Albir, 1996, 2001; PACTE, 2003). Finally, we present a proposal for an integrated model of the processes involved in reading as part of the process of literary translation which articulates van Dijk and Kintsch’s model with Holmes’s concept of map of the source text using the notion of translation competence as a bridge-concept between the models.

Keywords: literary translation, reading processes, text comprehension in translation.

Fecha de recepción: 14-09-2018. Fecha de aceptación: 19-11-2018.

Introduction

In this paper, we seek to show that van Dijk and Kintsch’s model of text comprehension (van Dijk, 1978, 1980, 2014; van Dijk & Kintsch, 1983; Kintsch, 1988, 1998) cannot account for the specific character that reading processes display when they are at the service of literary translation. This is by no means an attempt to undermine their model, which provides a solid, unified theory of text comprehension. Instead, what we will try to show is that reading, when it is part of literary translation, operates in a special way which seems to challenge some of the general processes described by van Dijk and Kintsch. As a solution, we will draw upon developments in the field of Translation Studies, which will provide the particular tools and categories we need to complement van Dijk and Kintch’s characterization of the processes of text comprehension. More specifically, we will use Holmes’s ([1978]1988) model of the translation process and focus on his concept of map of the source text. Though Holmes does not describe the nature of this mental representation or the processes he identifies, we believe his model is a powerful heuristic tool to address the peculiar nature of reading as part of the process of literary translation. Finally, we will incorporate Hurtado Albir (1996; 2001) and PACTE’s (2003) notion of translation competence as a bridge-concept that will allow the integration of van Dijk and Kintsch’s model with Holmes’s concept of map. At the end of this paper, we present our proposal for the description of the specific processes involved in reading for the purpose of literary translation.

Key concepts in van Dijk and Kintsch’s model of text comprehension: macrostructures, superstructures and levels of text representation.

Van Dijk and Kintsch’s model of text comprehension (van Dijk, 1978, 1980, 2014; van Dijk & Kintsch, 1983; Kintsch, 1988, 1998) offers a widely accepted explanation of the processes involved in reading and interpreting text. This interdisciplinary model, which emerged in the 1960s, draws upon contributions from the fields of psycholinguistics, cognitive psychology, artificial intelligence, social psychology, sociology, pragmatics, and social cognition, among others. A fundamental element in van Dijk and Kintsch’s model is the concept of macrostructure. The macrostructure of a text must be understood as an abstract representation of its global meaning, the theme, topic or gist of the text. Therefore, macrostructures have a semantic nature and they are composed of propositions. Macrostructures account for the overall coherence of a sequence of sentences and they play a key role in helping language users differentiate between texts and sequences of sentences which are not texts. Consider the following:

Following these authors, sequence a) constitutes a text because we can establish its global coherence; sequence b), on the other hand, does not fulfill the condition of global coherence and is not considered a text. This notion of coherence allows us to account for a great number of texts and situations. However, when we seek to apply it to literary texts, we encounter a series of difficulties. In effect, sequence b) may very well be an example of literary discourse, whose rationale responds to questions of a different nature. In William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (1929), the first seventy pages of the novel are narrated by Benjy, a thirty-three-year-old man with a mental disorder. Benjy’s discourse does not distinguish present from past and presents the characters and events of the novel in a very intricate way.

“Did you come to meet Caddy.” she said, rubbing my hands. “What is it. What are you trying to tell Caddy.” Caddy smelled like trees and like when she says we were asleep.

What are you moaning about, Luster said. You can watch them again when we get to the fence. Here. Here’s you a jimson weed. He gave the flower. We went through the fence into the lot.

“What is it.” Caddy said. “What are you trying to tell Caddy. Did they send him out, Versh.” (p. 14)

Benjy’s narrative is built upon its break-downs and “incoherences”, which serve to create a narrative voice that conveys Benjy’s fears, passions, and utter loneliness.

The fictional work of Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) provides numerous examples of the special character of the coherence that literary texts may display. Consider the following lines from Orlando: A biography (1928):

Green in nature is one thing, green in literature is another. Nature and letters seem to have a natural antipathy; bring them together and they tear each other to pieces. The shade of green Orlando now saw spoilt his rhyme and split his metre. Moreover, nature has tricks of her own. Once look out of a window at bees among flowers, at a yawning dog, at the sun setting, once think “how many more suns shall I see set”, etc. etc. (the thought is too well known to be worth writing out) and one drops the pen, takes one’s cloak, strides out of the room, and catches one’s foot on a painted chest as one does so. For Orlando was a trifle clumsy. (p. 10)

This passage presents two themes or dimensions simultaneously. One of these dimensions is related to the plot: the narrator tells us that Orlando feels unable to convey through his poem the color green that he sees outside, and reveals towards the end of the extract, and rather abruptly, that Orlando is a little clumsy. This information is presented at the beginning and at the end of the passage respectively. In the middle, the narrator hints at the ideas that nature supersedes art and experience supersedes observation. It is difficult to tell which dimension of the text, the more concrete and narrative or the more abstract and reflective, constitutes the main topic of the passage. Instead, Woolf jumps from one to the other assigning the same importance to both planes.

It is interesting to reflect on the peculiarities of literary discourse because they show that although the comprehension of literary texts depends on general processes of comprehension, these are not enough to account for the interpretation of passages like the ones we have cited. We can assign meaning to the passage from The Sound and the Fury or Orlando without being able to identify a global topic or gist. According to van Dijk and Kintsch, though, establishing the main theme is a crucial aspect of text comprehension and it is precisely through the construction of a macrostructure that we can come up with the overall topic of a discourse.

Following these authors, in order to obtain the macrostructure of a text and assign it a theme or topic, language users apply a set of macrorules strategically. The macrorules, which may be used recursively, allow us to identify the relative hierarchy of the different propositions in the text and access increasing levels of abstraction. Van Dijk & Kintsch (1983) identify three macrorules: DELETE, GENERALIZE, and CONSTRUCT.

The macrorule DELETE implies discarding unessential information which turns out to be unnecessary for the interpretation of the information that follows. The macrorule GENERALIZE establishes that we will substitute details with more general information; applying the macrorule GENERALIZE, we may replace the propositions

with the proposition

(iv) I bought some clothes[2].

The macrorule CONSTRUCT involves using our knowledge of the world to replace a series of propositions with one that expresses the whole meaning more succinctly. Consider the following propositions:

If we apply the macrorule CONSTRUCT, we may substitute propositions (i)-(vii) with the more economic (viii) I ate out.

Through the recursive use of the macrorules, language users build a hierarchical semantic structure which displays a series of cognitive advantages. In effect, the macrostructure provides: a) a common semantic base for the propositions of a text; b) a relatively simple structure which may be kept in our STM (short term memory); c) a tool for the hierarchical organization of the information in EM (episodic memory); d) a tool to update information in longer texts; e) fundamental clues to reactivate necessary semantic details; f) an explicit construction which bears semantic properties which are more important than a discourse or episode.

So far, we have briefly described the nature and functions of macrorules and the importance of macrostructures in the processes of text comprehension. However, what happens when reading is part of literary translation? The translator-reader must see to all the information in the source text, whether this be central or additional. This implies, in a way, disregarding the macrorules DELETE, GENERALIZE and CONSTRUCT in order to focus on all the elements of the text, which the translator-reader will have to recreate in the target text.

Apart from the macrostructure, some texts have global patterns of organization that van Dikj and Kintsch call superstructures. These structures have a schematic nature and they consist of a series of conventional categories which organize the text as a whole. The concept of superstructure determines, among other things, our awareness that texts may have introductions and conclusions and that the former appear at the beginning and the latter appear at the end of texts. As it is, superstructures may operate as the discursive conventional functions of the macrostructure and may be thought of at a kind of global syntax of the discourse.

Another central aspect of van Dijk and Kintsch’s model is the distinction between different levels of text representation: superficial structure, text base and situation model. The superficial structure comprises the linguistic and grammatical properties of a text and contains the words expressed in the text directly. And, as words express propositions, they lead us to the second level of text representation. The text base is represented by the sequence of propositions expressed by the sequence of sentences of a text. A key concept in the analysis of the text base is coherence. In effect, the relations which are established between the propositions of a text and the facts that these evoke account for the local relations of coherence at the level of the text base. The most direct way to establish if a sentence makes sense is to analyze if it may constitute an imaginable fact in our psychobiological world or in a possible world. Facts manifest themselves as events, actions, states or processes so that a text sequence of propositions must denote an imaginable sequence of events, actions, states or processes in a possible world.

The notions of fact and imaginable fact display a singular character when we consider literary discourse. Undoubtedly, one of the most distinctive aspects of literary texts is that they create their own possible worlds and they multiply infinitely the possibilities of what we may consider imaginable. The list of fictional works that we may use to exemplify this characteristic of literary discourse is endless. Ursula Le Guin’s feminist novel The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) describes a planet inhabited by ambisexual individuals and recreates their habits and culture. The story “Funes, el memorioso” (1944) is an example of Borges’s great capacity to help us conceive the impossible. In this story, Funes’s perception and memory are infallible; he can remember how every leaf of every tree looks different at different times of the day and the experience of looking at it or imagining it.

The reader’s imagination is also put to the test when we read literary texts associated with cultural groups or communities who differ from our own direct experience of the world. Yukio Mishima´s celebrated story “Patriotism” (1960) describes in great detail the ceremony of hara-kiri that ends with the life of Lieutenant Shinji Takeyama. As the story unfolds the reader bears witness to the ritual of disembowelment that Takeyama carries out in front of his wife and in honor of the Imperial Army. Mishima’s story presents an array of objects and events whose interpretation poses a challenge for a reader who is unfamiliar with the culture and history of Japan. In fact, one of the greatest difficulties that students of literary translation face consists in identifying and interpreting the cultural aspects of the source text. In effect, we have observed that when faced with realities which are culturally dissimilar to their own, student translators have great difficulty in making sense of them and recreating them adequately in the target text.

So far, we have described van Dijk and Kintsch’s first two levels of text representation; the superficial structure and the text base, and we have defined the former as the words expressed in the text directly and the latter as the relations between the propositions and the facts denoted by the text. When we analyze literary texts in relation to the notions of superficial structure and text base, at least two problems arise. According to van Dijk and Kintsch, the actual words from the text are “discarded” as soon as the information is elaborated in the form of propositions. We will argue, however, that literary discourse challenges the supremacy of the text base over the superficial structure as it confers fundamental importance to aspects of style, lexical choice, literary and rhetorical resources. The other problem is related to the text base. After all, we may wonder whether establishing propositional relations of coherence is enough in order to make sense of literary texts.

Van Dijk and Kintsch’s third level of text representation is the situation model, which consists of a mental representation of the text and combines the information from the text with the reader’s knowledge. This aspect of the reading process is crucial to our interests because the literary translator needs ample knowledge and experience in the source and target language-cultures in order to interpret the source text and recreate it in the target text. The situation model is a major challenge for the student translator, who may not be ready to provide the kind of knowledge necessary for the construction of an adequate situation model for the source text and may have difficulty constructing the source text as a result.

The model of text comprehension proposed by van Dijk and Kintsch, which explains the reading processes of the non-translator reader, does not allow us to address the specificity of the reading processes involved in literary translation. We believe that in order to account for these processes we must bring together van Dijk and Kintsch’s model with developments from the field of translation studies.

Developments in the field of translation studies: Holmes, Hurtado Albir and PACTE.

In a famous essay, James S. Holmes ([1978]1988) criticizes the popular idea that translation is carried out word by word or sentence by sentence. Instead, he suggests that there are two planes in translation: a serial plane and a structural plane. In the serial plane, the translator deals with the source text word by word and sentence by sentence while in the structural plane he/she constructs a mental representation of the source text as a whole. Holmes calls this mental representation map of the source text and describes this map as a construct which contains very diverse information. As a linguistic artifact, the map contains information about the linguistic continuum the text belongs to (contextual information). The map is also a literary artifact and as such it includes information about the literary continuum the source text is identified with (intertextual information). As a sociocultural artifact, the map contains information about the text in relation to the sociocultural context in which the text is set (situational information).

Even if Holmes does not describe it in much detail, this conception of the source text is enlightening as it shows that reading in literary translation is an informed process that requires specific kinds of knowledge. The notions of linguistic, literary and sociocultural artifact trigger questions which are, in our opinion, inescapable for the literary translator: what kind of linguistic choices has the author of source text made? How does the source text interact with other literary expressions and traditions? Which sociocultural elements does the source text display? These questions must be answered by the literary translator and, as we see it, must be addressed in the teaching of literary translation.

Unfortunately, Holmes does not identify the elements involved in the structure of the map of the source text and how these are related to one another or the processes which allow for the construction of the map, the abilities that are needed, or the strategies that come into play. Instead, he theorizes that the translator applies a set of derivation rules. Though Holmes does not describe the nature of these rules or how they function, he suggests that they are the same rules a regular reader applies. In our view, however, reading for the purpose of literary translation displays processes and abilities which are specific to this activity.

It is precisely these gaps that encourage the integration of Holmes’s and van Dijk and Kintsch’s models that we propose as a way to better describe the processes involved in reading as part of the process of literary translation. While Holmes’s model provides a description of the processes involved in literary translation, he does fully describe the components of the model and the nature and operation of the mental representations and rules involved. Van Dijk and Kintsch’s model, on the other hand, provides a detailed description of the mental representations and the processes involved in text comprehension but cannot account for the specificity of reading as part of the process of literary translation. As a result, we propose an articulation of both models and use of the notion of translator competence as our bridge-concept.

PACTE and the concept of translation competence

Holmes held the view that the reading processes involved in literary translation were the same as those involved in reading literary texts for any other purpose. However, the translator displays a set of knowledge and abilities which are specific and are employed in the reading processes involved in literary translation. Hurtado Albir (1996, 2001) and PACTE (2003) have identified and described this knowledge and abilities as translation competence. From this perspective, translation is a complex task of a non-linear nature and it integrates controlled and non-controlled processes. Translation entails problem-solving tasks, decision-making and the use of strategies. In this context, PACTE’s main interest consists in identifying the knowledge and abilities that distinguish the translator from a non-translator bilingual subject and propose the term “translation competence” to integrate this knowledge and abilities. According to PACTE, it is the translator’s translation competence that allows them to carry out the cognitive operations in the translation process.

Translation competence is defined in relation to a system of six sub-competences. Bilingual sub-competence comprises the pragmatic, psycholinguistic, textual and linguistic knowledge which are necessary for communication in two languages; this knowledge is mainly operative. Extralinguistic sub-competence contains essentially declarative knowledge in relation to the source and target cultures, the world and specific fields. Knowledge about translation entails declarative knowledge about the principles and norms that guide translation as a professional practice. The knowledge related to the use of documentation sources and communication and information technology applied to translation is integrated in the instrumental sub-competence. The strategic sub-competence controls the translation process and is composed of the operative knowledge needed to guarantee the efficacy of the translation process and solve the problems that may arise. There are also some psycho-physiological components which are necessary in the translation process. Some of these components are: perception, memory, attention, emotion, intellectual curiosity, perseverance, confidence, creativity, and motivation, among others.

Towards an integrated model for the description of reading processes involved in literary translation

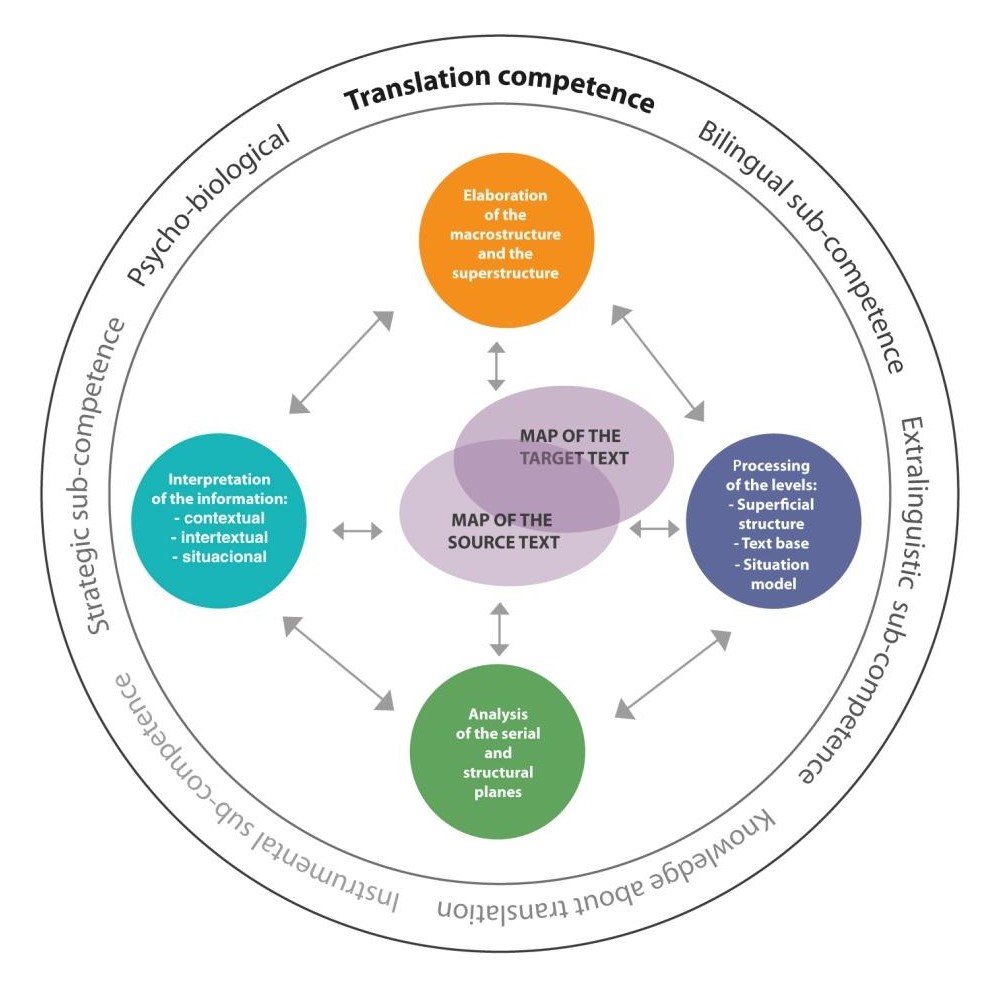

The model we present in this section constitutes an integration of van Dijk’s model of text comprehension and Holmes’s translation model and uses PACTE’s translation competence as a bridge-concept.

The translation process begins, according to Holmes ([1978]1988), with the construction of a map of the source text, which is the result of the use of derivation rules. Holmes does not characterize these rules. However, van Dijk and Kintsch’s model (van Dijk, 1978, 1980, 2014; van Dijk & Kintsch, 1983; Kintsch, 1988, 1998) can shed light in relation to this point. We believe that the notion of map of the source text may be thought to include the construction of the macrostructure and the superstructure as the global structures of meaning and form of the source text. The construction of the map of the source text also entails the elaboration of the different levels of text representation described by van Dijk and Kintsch: superficial structure, text base and situation model. At the level of the superficial structure, the reader-translator elaborates the source text in its linguistic and grammatical aspects. The text base implies the interpretation of the sequence of propositions of the source text and the situation model allows for the integration of the information from the source text with the reader’s knowledge of the facts evoked in the source text. The situation model is, therefore, the virtual space where translation competence operates. The situation model also allows the reader-translator to integrate the different kinds of information that, according to Holmes, are part of the source text: contextual information from the text as a linguistic artifact; intertextual information about the text as a literary artifact and situational information about the source text as a sociocultural artifact. Holmes’s concept of serial plane, which is related to the word-by-word translation of the source text, is based on the superficial structure whereas the structural plane of the translation process is related to the elaboration of the text base and the situation model. Figure 1 presents a diagram that illustrates the integration of the models presented by van Dijk and Kintsch (van Dijk, 1978, 1980, 2014; van Dijk & Kintsch, 1983; Kintsch, 1988, 1998), and by Holmes ([1978]1988) in which the notion of translation competence described by Hurtado Albir (1996, 2000) and PACTE (2003) functions as a bridge-concept which enables the processes involved in the model.

Figure 1

At the center of the figure we can see the map of the source text, whose construction is the main component in the reading comprehension processes involved in literary translation. Around the map of the source text we have identified the processes which are implied in this construction: a) the elaboration of the macrostructure and the superstructure of the source text; b) the processing of the different levels of text representation of the information in the source text: superficial structure, text base and situation model; c) the analysis of the source text in its serial and its structural planes; and d) the interpretation of the source text as a linguistic, literary and sociocultural artifact. Translation competence appears as a circle that contains the processes identified as these require the sub-competences which are part of translation competence: bilingual sub-competence, extralinguistic sub-competence, knowledge about translation, instrumental sub-competence, strategic sub-competence and psycho-biological components.

Conclusion

The integration of models we propose offers a more in-depth description of the nature of the processes involved in reading as part of the process of literary translation than both models can provide on their own. We believe our proposal for an integrated model of reading in literary translation allows us to account for the complexity and the specificity of the processes we have identified and constitutes a powerful tool to reflect on the challenges faced by students of literary translation.

References

Holmes, J. S. ([1978]1988). Describing Literary Translations. In J. S. Holmes (Ed.), Translated!: Papers on Literary Translation and Translation Studies. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Hurtado Albir, A. (Ed.). (1996). La enseñanza de la traducción. Castelló: Universitat Jaume.

Hurtado Albir, A. (Ed.). (2001). Traducción y traductología: Introducción a la traductología. Madrid: Cátedra.

Kintsch, W. (1988). The use of knowledge in discourse processing: a construction-integration model. Psychological Review, 95, 163-182.

Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: A Paradigm for Cognition. Cambridge: CUP.

van Dijk, T. A. (1978). Tekstwetenschap. Een interdisciplinaire inleiding [La ciencia del texto. Un enfoque interdisciplinario]. Amsterdam: Het Spectrum.

van Dijk, T. A. (1980). Estructuras y funciones del discurso (M. Gann & M. Mur, Trans.). Bogotá: Siglo XXI.

van Dijk, T. A. (2014). Discourse and Knowledge: A Sociocognitive Approach. Cambridge: CUP.

Van Dijk, T. A. & Kintsch, W. (1983). Strategies of Discourse Comprehension. San Diego: Academic Press.

[1]* Profesora en Lengua y Literatura Inglesas de la Universidad Nacional de La Plata (UNLP) y ha completado la Maestría en Psicología Cognitiva y Aprendizaje de FLACSO (tesis en proceso de evaluación). Correo electrónico: doloresaicega@gmail.com

Ideas, IV, 4 (2018), pp. 1-13

© Universidad del Salvador. Escuela de Lenguas Modernas. Instituto de Investigación en Lenguas Modernas. ISSN 2469-0899

[2]. We have not used more elaborate forms of propositional notation in order not to complicate the presentation unnecessarily.