Teaching writing in the ESL/EFL context: some myths and truths about contrastive rhetoric

Ana Soledad Moldero[1]*

Universidad Nacional de La Plata

Universidad de Belgrano

Argentina

Resumen

Al abordar la escritura en contextos académicos de nivel superior en la enseñanza del inglés como L2/LE, se observa que la retórica del inglés plantea dificultades a los estudiantes cuyos estilos retóricos son ajenos al inglés. La retórica contrastiva (RC) informa acerca de las retóricas de culturas no angloparlantes y permite comprender los problemas de producción de textos en inglés (Kaplan, 1966; Connor, 1999). Los trabajos subsiguientes señalan la necesidad de que las producciones escritas en inglés se adapten al estilo retórico de la cultura angloparlante (Connor, 2002, 2008; Matsuda & Atkinson, 2008). Esta postura conlleva ciertos peligros: podría ser considerada una nueva forma de ‘orientalismo’ (Said, 1978; Pennycook, 1999) por aquéllos cuyas tradiciones retóricas son ‘la otredad’; a su vez, los estudiantes de inglés como L2 /LE parecen “resistirse” a la retórica del inglés. En este trabajo examino estas cuestiones, exploro la relevancia de la RC para los profesores de inglés como L2/LE y sostengo la necesidad de incorporar la dimensión de género discursivo a través de la teoría de género (Swales, 1990, Bhatia, 2004) para lograr una mayor comprensión y alcance de la enseñanza de la escritura en contextos académicos de L2/LE. Afirmo que a pesar de las imputaciones de etnocentrismo y demás reservas justificadas, la RC, redefinida como retórica intercultural (IR), es un instrumento válido en el campo de la lingüística aplicada para predecir, reconocer y evaluar los problemas de escritura en inglés.

Palabras clave: escritura, inglés como L2/LE, retórica contrastiva, género discursivo, expectativas culturales, discurso orientalista, conciencia genérica transcultural

Abstract

When dealing with ESL/EFL writing in academic contexts at higher education, teachers observe that adjusting to English rhetoric poses a number of challenges to students whose rhetorical styles are non-English. Contrastive rhetoric (CR) has informed about the rhetorics of cultures other than English-based ones (Kaplan, 1966; Connor, 1999) and has offered some insights into students’ problems when it comes to composing English texts. A body of subsequent research has pointed to the need to have ESL/EFL writers adapt to the rhetorical style of the English-speaking culture (Connor, 2002, 2008; Matsuda & Atkinson, 2008). This approach is not without pitfalls: it might be understood as a new form of ‘Orientalism’ (Said, 1978) by rhetoricians whose rhetorical traditions are ‘the Other’ and, in turn, ESL/EFL writers tend to “resist” English rhetoric. In this paper I address these issues, explore the relevance of CR for ESL/EFL practitioners and discuss the need to rely on genre analysis writing (Swales, 1990, Bhatia, 2004) to gain in insight and scope in the teaching of writing in academic ESL/EFL contexts. I argue that despite claims of ethnocentrism and other justified reservations, CR, redefined as intercultural rhetoric (IR), proves a valid instrument in the applied linguistics field for predicting, spotting and evaluating ESL/EFL students’ composition problems.

Keywords: ESL/EFL writing, contrastive rhetoric, genre, cultural expectations, Orientalist discourse, cross-cultural generic awareness

Fecha de recepción: 5-8-2019. Fecha de aceptación: 10-10-2019.

Introduction

It has been fifty years now since Robert Kaplan’s (1966) seminal paper on contrastive rhetoric first came out as a contribution to the teaching of writing in ESL. In this influential article Kaplan observed that essay writing by his ESL students displayed certain culture-related regularities in their construction patterns that ran counter to tutors’ expectations. Kaplan concluded at the time that languages had inherent rhetorical traditions and peculiar thought styles that would tend to come through in writing (Connor, 1990, p. 5) and, despite some serious criticism to his original approach, contrastive rhetoric (CR) became established as a discipline in its own right.

For over three decades now CR has been the subject of much debate and ongoing reflection. It has also turned into a site of tension between its original ESL pedagogical orientation and its broader, genre-related theoretical implications (Connor, 1999, pp. 18-22; Connor, 2002, p. 497). Current academic discussions on the role and directions of present-day CR seem to have left behind former controversies and objections over its early associations with error and contrastive analysis of L1 versus L2, its static view of L2 learning, its structuralist bent or its ethnocentric, English-centred approach to languages (Connor, 1999, p. 16). Following Kaplan’s own redefining of his theory and a body of research into the issue, most notably Connor’s (1999), the CR debate now seems to be moving on towards a more refined consideration of its future course.

All the same, CR has contributed greatly to an awareness of non-native students’ problems when writing in ESL/EFL academic settings. In this paper I will argue: (a) that from the point of view of applied linguistics, and despite criticisms, CR still makes a valid instrument for predicting, identifying and understanding ESL/EFL students’ composition problems; (b) that while its ethnocentric methodological approach must be viewed with reservations, to regard CR as a new form of ‘Orientalism’ is a narrow or chauvinistic take on the workings of culture; (c) that by exploring differences in rhetorical expectations and conventions among cultures, CR can create a sounder frame of reference and advance broader, more realistic assessment criteria for ESL/EFL practitioners –both native and non-native, but particularly the latter– to contribute to achieving adequate students’ results in expository-argumentative writing.

Contrastive rhetoric: dealing with difference

On devising his innovative study, Robert Kaplan’s concern was to pinpoint the problems revealed by international students when constructing their ESL academic essays and help improve the quality of their writing (Kaplan, 1966).Besides interlanguage errors and other inadequacies at the textual level –syntactic, grammatical or lexical–, possibly the result of limited language proficiency, Kaplan identified patterns of text organisation that differed from the standard expectations of academic expository writing. He then claimed that "each language and each culture has a paragraph order unique to itself, and … part of the learning of a particular language is the mastery of its logical system" (Kaplan, 1966, p. 14).Kaplan had a distinct teaching focus in mind –he was trying to establish some clear, unmistakable differences between English and other cultures, in the belief that such insights could make the basis for some sound pedagogical approach to writing in ESL academic contexts (Kaplan, 1966, pp. 20-21).

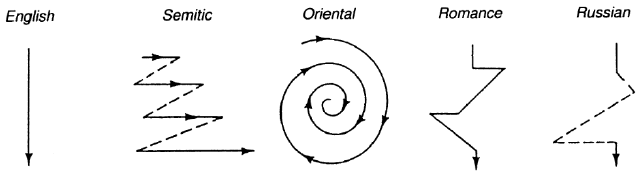

In what he himself would downplay in a later paper (Kaplan, 1988) as his doodles article, Kaplan (1966) generalised his observations on the rhetorical organization of expository paragraphs in five culture groups. His characterisation established a linear development for Anglo-European essays, a pattern of parallel coordinate clauses for Semitic languages, an indirect approach for Oriental languages, where the topic is looked at tangentially from different standpoints, a rambling development that allows a certain amount of digression and loosely relevant material in Russian and in Romance languages. The culture-specific patterns that have come down to us are as follows:

Figure 1 Cross-cultural differences in paragraph organization in Kaplan (1966) study on thought patterns in intercultural education.

However, as can be seen from the rough and ready account of features observed, the cultural traits Kaplan laid down in his 1966 article do not follow neat analytical categories. The descriptions address such diverse criteria as rhetorical staging (unfolding through a typical pattern of goal-oriented moves), topic focus, information ranking, information distribution, syntactic complexity, sentence length, all of which should be kept separate for the sake of a more informative analysis. Precisely, Connor (1999, pp. 16-27) proposes to expand the scope of CR and bring into play other related disciplines –situated composition studies, L2 writing processes, text linguistics, contrastive genre analysis, ideology-based rhetorical traditions- in order to exploit their contributions to CR and arrive at a more inclusive and flexible framework for analysis. This new model has a fresh cognitive and socio-cultural emphasis to it. In other words, there is an increasing interest in the writing process and purposes as well as in the product of writing, an acknowledgement of the influence of linguistic relativity and a generally more comprehensive view of the rhetoric of different cultures.

Contrastive rhetoric and the concept of genre

One particularly stimulating shift in focus concerns the genre dimension applied to CR Indeed, Connor (2008, p. 313) claims that the definition of ‘rhetoric’ in CR as a manner of text organisation and style must be expanded beyond its classical characterisation to include the communicative purpose. This author quotes the work of several genre analysts in order to show the concept of genre is directly relevant to the CR discussion (Swales, 1990; Berkenkotter & Huckin, 1993; Bhatia, 1993). All these researchers would subscribe to the fact that genres are dynamic constructs, staged goal-oriented social processes on the one hand, and the product of culture on the other hand, conventionalised by communicative use. In this way the communicative dimension of CR becomes firmly attached to the notion of genre.

Furthermore, genre knowledge is a form of ‘situated cognition’, rooted in everyday communication and mediating between typical features of individual contexts and some others that repeat themselves across various domains- domestic, professional, academic, institutional (Berkenkotter & Huckin, 1993). They are recognised and legitimised by the expert members of a discourse (academic or professional) community as fulfilling the rationale for the genre, which constrains ‘the allowable contributions in terms of [genre]… content, positioning and form’ (Swales, 1990, p. 52). For Bhatia (2008) the rationale is the notion of generic integrity, that is, a ‘socially constructed typical constellation of form-function correlations’ (Bhatia, 2008, p. 123). This distinct setup of features and functions realises a specific communicative goal. In turn, this communicative purpose is a privileged criterion as it keeps the scope of a genre ‘narrowly focused on comparable rhetorical action’ (Swales, 1990, p. 58).

Teaching ESL/EFL composition -applications and limitations of CR

A sensible approach to the teaching of writing, then, should draw on a comprehensive model of CR that centres on genre analysis. In the first place, surface textual features easily become apparent to the composition or rhetoric teacher and are worth looking at. Sentence length and subordination, grammatical accuracy and cohesion, lexical appropriateness and stylistic consistency, all make the stuff of every ESL/EFL teacher’s business. However, the perceived rhetorical staging of a text and the communicative aims associated to it may not come out so neatly. Tutors and students need to become aware of the logics behind preferred modes of unfolding towards particular rhetorical goals.

Of course, it is essential to be able to recognise common patterns of text organisation (clause-relation patterns, text sequences, text superstructures (schematic) and macrostructures (thematic) (van Dijk, 1980). On the other hand, neither teachers nor students in a community of practice will develop a true awareness of generic cross-cultural divergence, unless they can perceive intended communicative goals for the genres and acceptable ways of attaining such goals on a larger, discourse level. One problem students tend to encounter is the mistaken view that there is one ‘right’ way of writing an essay or other texts, which also often relies on structural considerations. As Swales (1990) explains, it is the rationale behind the genre that shapes the schematic structure of the discourse and imposes constraints on rhetorical patterns and style. But then again, these should be looked at not only across genres but also across different cultural environments and traditions.

Now, a further question for the writing instructor to consider is that of variability among genres. Whereas some are highly structured, more register-dependent, such as the legal genres, others are more flexible and likely to attract personal variation and even invite flouting of canonical forms. Forms of the personal account and creative narrative-descriptive writing, for example, –or textual sequences of such rhetorical mode embedded in expository-argumentative genres– tend to allow for much greater flexibility and idiosyncratic variation within the typical spatio-temporal narrative staging than does, perhaps, formal argumentation.

Unlike narrative writing, academic writing relies on formal argumentation. A type of persuasive discourse, it has evolved out of Western classical rhetoric and has its peculiar ways of unfolding. Based on Aristotelian persuasive appeals –logos, ethos and pathos[2]- and the five Roman canons[3], formal academic arguments present recognizable patterns to those who have been exposed to classical argumentation in Western culture. This is particularly interesting when assessing expert members’ expectations. Naturally, then, a given academic community –tutors, editors and fellow members- will have expectations as to the organization and style of academic texts.

Moreover, genres also vary in their prototypicality. Different exemplars of a genre display various degrees of correspondence with the prototypical linguistic features for the genre (Swales, 1990, p. 49). Now these differences do not stem only from cultural traditions in the strict sense of the concept. There are also individual and social factors involved, many of them ultimately cultural as well, to do with amount of exposure to a genre class, level of L1 instruction and education for native speakers. In addition to these, exemplars often vary in the degree of L2 proficiency for non-native writers, amount of exposure to and rate of exchange within a given academic or professional genre community and even personal talent or skill.

For that reason, CR case study methodology would require further matching of informants’ variables and quantitative designs –including statistical analyses– so as to contribute reliable generalisations based on cultural traits. So far, cross-cultural studies have come up with prototypes for a range of academic and professional genres (Connor, 1999, pp. 148-149). Besides an awareness of goal, form and content, genre knowledge involves a sense of rhetorical appropriateness that has to be fulfilled beyond a certain rhetorical threshold. Two questions seem to be at stake here: on the one hand, spotting the prototypical features of the genre rationale for both L1 the L2 and deciding which features would be simply desirable, rather than essential; on the other hand, determining whichL1 features would be incompatible with the L2 genre rationale. In fact, when it comes to identifying and dealing with ESL/EFL students’ composition problems, CR comes forward as a valid reminder of the trends displayed by various exponents in different cultures. Indeed, I believe it is a sound informative tool for predicting and detecting inadequacies with a view to addressing them.

Contrastive rhetoric– a new form of ‘Orientalism’?

Despite its valuable findings for ESL/EFL, CR has been the target of criticism over its alleged Orientalism, particularly from rhetoricians belonging to non-English traditions. In order to consider to what extent CR could be viewed as a new form of Orientalism, I would first like to briefly examine the unfolding and scope of the concept.

The term Orientalism is traditionally associated with Western cultural imperialism today. British colonialism was at first characterised by a respectful but patronising attitude towards native people in colonial territories and, prompted by the idea of the noble savage[4], it was tolerant of the local languages, religions and ideologies. The older concept of Orientalism, then, stems from this kindly approach to cultures other than European, which attempted to study and protect the literary and artistic productions, religious thought and traditional social life of the colonised.

However, the early 19th century saw the emergence of Anglicism, which meant, roughly, imposing English education policies on moral and economic grounds. With this shift, the concept took on a new ring to it and became the opposite ideology: promoting education in the local languages, even at the expense of widening the gaps in the social fabric. And, as Pennycook (1999, p. 74) claims, the two ideologies worked side by side and complemented each other. Ultimately, there was a direct correlation between imperialising an elite in order to facilitate the demands of trade and government and raising a mass of less apt individuals to constitute a workforce better suited to take part in the colonial economy. Both existed alongside each other, and neither could thrive without its counterpart.

Indeed, the spread of English in colonial Britain was enforced just as much through coercion by colonial state forces as through local endorsement of the Orientalist discourse (Pennycook, 1999). Said (1978, pp. 26-27) claims that the Orientalist discourse seeps into the discourse practices of education and science and thus the idea of a superior West over an inferior East goes unchallenged through disciplinary knowledge (Said, 1978, p. 44). Through art, literature and cultural studies, the discourse of Orientalism creates a set of clichéd beliefs, ideological suppositions and fantasies about this abstraction labelled the Orient, a mythical, prefabricated construct that stands in binary opposition to Western discourse (Said, 1978, p. 49; 95).

Along these lines, English earned its place as the language of academia. Just as access to English served to mitigate power asymmetries between the Indian elites and their British rulers in 19th century colonial India, so English came to be hailed by the international academic community as the means to increase the visibility of world thought and research. And, in the process, Foucault would argue, English as an International language (EIL) rose as the eye of the panopticon[5] (Foucault, 1977, as cited in Pennycook, 1999). Through English, mainstream knowledge dominates other forms of cognition and cultural expression and, in turn, the uses and practices of English set the standard. Indeed, the currency of English in international academic and scientific circles today, and the social and economic prestige associated with it, would seem to be reviving the Orientalist case.

Over the last 30 years or so, Orientalism has adopted a normative tone and the new concept of Orientalism has taken on a negative meaning. Arguably, Orientalist studies work on an idealised, often biased, view of the East, relying on a few traits that become fixed in a comfortable, oversimplified image of the ‘Other’. As is the case with all stereotypes, otherness comes to be viewed as an essentially static notion, as a cultural construct, a commodity, as it were, to be used by the West for its own convenience. It is within this ongoing debate that the controversy over the purported Orientalism of CR must be examined.

In the views of those belonging to rhetorical traditions other than the Anglo–American tradition, there is the suspicion that the so-called Anglophile nature of (early) CR may be enacting a new form of control through hegemonic discourse. The controversy stretches over to rhetoricians of Anglo-European backgrounds who are daunted by the thought -and by a sense of colonial guilt, perhaps- that they may be encroaching on other cultures’ products and traditions and eventually stifling them. Connor (2002, 2008) reports a number of criticisms brought against CR: a lack of sensitivity to cultural differences; a marked preference for Anglophone academic style -as the very study of differences gives away; an expectation that academic expository-argumentative writing should conform to rhetorical and stylistic forms that please the Anglo-American eye. Others also criticise the East-West cultural dichotomy, which may lead to the implicit belief in the superiority of Western writing. Indeed, the claim that English rhetoric is “linear” -and therefore logical- whereas those of other cultures are not would seem to suggest a belief in the intellectual superiority of the English culture. While the former criticisms are well justified, it is also true that by the very nature of culture, all cultures -directly or indirectly- apply pressure to conform.

CR purported Orientalism

It is fairly obvious in the first place that the criticisms levelled against CR concern the bad Orientalism, according to which CR would be a hegemonic tool for ideological colonisation and eventually for domination through power-knowledge[6] (Foucault, 1980). Said does not explicitly mention CR, but he suggests that much academic scholarship in the West is Orientalist, since it relies on Eurocentric assumptions and biases when it addresses other cultures and communities. Now then, in view of the objections from post-modernist critique, what claims can be made to support the alleged Orientalism of CR?

As I see it, these criticisms could be analysed from at least two broad standpoints -theoretical-ideological or practical-pedagogical, each of them with different implications. I think the former presents three key aspects concerned with Orientalist discourse that would permit an analogy with the criticisms against CR: the question of stereotyping, the idea of inadequacy, and the need for what I will name salvation from inadequacy. However, from a practical-pedagogical point of view, one could hardly level charges of Orientalism on a methodological perspective that serves the purpose of clarifying the matter for ESL/EFL writing instructors and students.

As regards stereotyping the rhetorical styles of the Other, if Kaplan’s sketchy patterns were to be taken at face value, we would have to admit, indeed, they amount to sweeping generalizations about some vast, complex cultural traditions. We would also have to acknowledge that because of their oversimplified nature they miss out on significant nuances and become stale notions, fixated in time and devoid of individual richness. Individuals and cultures evolve as they incorporate new layers of experience and integrate them dynamically into the culture and, by necessity, into their rhetorical traditions- stereotypes do not. They are unable to adapt to changing circumstances and therefore remain forever incomplete. This is what Edward Said would call essentializing the Other -making them fixed in their essence– thus denying them the possibility of existing, that is, evolving in time and space.

A direct result of stereotyping is the idea of inadequacy. The group or culture represented as inadequate or deficient consequently requires someone to put that inadequacy right. It needs improving or polishing, naturally by those who ‘know better’. And, coupled with this unfortunate outcome is another danger associated with stereotyping: abstract, incomplete categories are taken for objective knowledge. This in turn often leads to the dubious conclusion that possession of that knowledge entitles a group to some superiority over an inadequate, inferior Other, who comes in for what I have named salvation from inadequacy. Just as the East needed civilising, the would-be inferior culture needs to be saved from its inadequacies. But in order to be saved it will have to agree to some constraints, which takes us to the idea of power and domination of the Other.

So then, from this ideology-laden, post-modernist standpoint, one can see why CR has been stigmatised as Orientalist, as an instrument of control enacted through Orientalist practices. Writers from non-English rhetorical traditions amount to the Other and are therefore inadequate in their rhetorical manner. Their ‘defects’ must be corrected so as to meet the expectations of Anglo-American style, to gain acceptance in the academic world, even at the expense of having to yield matters of personal style or cultural identity, or temper idiosyncrasies, or even supress intended personal meanings. Orientalist discourse, Said would warn, is instilled into academic ideas and practices and thus the Anglo-European superiority becomes a foregone conclusion.

From the practical-pedagogical point of view, though, it would not be fair to accuse CR of Orientalist. Despite its bias in favour of the Anglo-European rhetorical tradition, it started off with a true concern with teaching composition in academic settings. Since then it has tried to raise an awareness of the rhetorical expectations of Anglo-European circles so as to help students become more competent in their writing practices and thus more effective when getting through to English-speaking audiences. In this sense, CR can equip ESL/EFL students and tutors with methodological tools for students to develop greater genre compliance in academic settings and then become more successfully empowered by their English educations.

Problems adjusting to rhetoric- ESL/EFL writers’ resistance or lack of awareness?

It is fairly common for the ESL/EFL practitioner to notice a certain ‘resistance’ on the part of novel ESL/EFL writers to conform to expected rhetorical standards. Whether consciously or not, non-English writers’ productions fail to closely adjust to conventional English rhetoric. This is particularly so among the less involved, insightful or committed members of an academic discourse community.

As a writing instructor in the EFL field, myself, I often see undergraduate students’ writing fit oddly into typical or accepted rhetorical patterns or flout them altogether. Even at high levels of English proficiency, errors in grammatical accuracy or lexical appropriacy may persist in some cases. A number of students tend to show stylistic inadequacies as well. Finally, it is quite clear in some cases that even trainees with a high level of linguistic competence have trouble developing arguments adequately.

Quite apart from grammatical accuracy and lexical appropriacy, which are directly related to students’ levels of EFL proficiency, I have observed -even if informally- various kinds of clumsy expression in the course of many years’ practice as an EFL tutor. Some of these problems are:

Of course, while much of this clumsiness is due to inadequate linguistic competence, especially at the lower discourse levels –lexico-grammar– certain stylistic aspects require greater, more refined linguistic or communicative sensitivity. Now, explanations of rhetorical or generic mismatches may require going beyond the linguistic command of the code into the cultural domain, which is where genres belong.

In fact, genre knowledge is ‘background knowledge of the rhetorical structures of different types of texts’ (Carell, 1983, as cited in Swales, 1990, p. 85). Genres constitute formal schemata, that is, assimilated direct experiences and linguistic textual experience acquired mainly through schooling and cultural exposure (Swales, 1990, pp. 84-85). They are embedded in the culture -that is why discourse communities set up academic, social or cultural expectations for the genre, including the ideological dimension. They demand typical patterns of text organisation and certain rhetorical moves associated with the genre besides placing stylistic constraints in terms of surface features.

Naturally, not every non-native ESL/EFL writer will shun the expected conventions. It is generally the poorly equipped ones who will, since the greater the communicative competence students have, the deeper their cultural knowledge and the more culturally sensitive they are. Highly competent EFL students are quicker picking up cultural clues and are therefore more likely to adjust or accommodate at will, usually efficiently, to the contextual requirements imposed by the academic/social situation.

On the other hand, the question of resistance is a complex one and the modest scope of this paper does not allow me to exhaust the multiple factors at play. I will just speculate that attitudes towards the demands of EFL academic rhetoric -whether agreeing to or resisting it- may be both conscious and unconscious. Either way, I believe a major determining factor of these reactions is the individual’s existing formal schemata about the sort of rhetoric the situation calls for.

Conscious and unconscious resistance

Non-native EFL writers’ reluctance to comply with expected English rhetorical patterns is expressed, for example, when trainees stubbornly insist on ‘doing things their own way’. They seem to have the feeling that their way of writing is not merely the natural way –it is the only way there is to it. While they are not fully aware of some apprehension, they may feel that the proposed pattern is alien to them and could even contradict their very essence. This mild unwillingness seems to warn that adhering to it would mean conspiring against their individual non-native identity.

On the other hand, there might also be a conscious unwillingness to comply. This refusal to adhere to prescribed composition patterns may be rooted in a desire for ‘free’ unrestrained self-expression, both in content and in form, a craving for some uniqueness that the student associates with originality and an unmistakable identity. Whether native or non-native, students who strive to be original without enough generic awareness face an almost impossible task. Eventually, they sacrifice the important for the original.

These inexperienced writers overlook a number of things. This ‘freedom’ is not such, in the first place: it is culturally determined by exposure to the texts and genres that were part and parcel of their upbringing, the kinds of social and institutional interactions they engaged in within their discourse communities and the kinds of explicit composition training they received through schooling.

Secondly, while it is true that the conventions of expository-argumentative academic writing in English may be unfamiliar and even daunting, what students cannot see is that this unexplored area is just that: a cultural product they can appropriate and make their own just as much as every native speaker has done in the course of their education. By the same token, it may well be the case that native speakers outside a certain community of practice feel that a given genre is just as alien to them, if not more, than it is for a non-native user of English. What is more, a non-native writer who has been initiated into the genre by sharing in an ESL/EFL academic discourse community may be better equipped in this respect than a lay native-speaker.

Helping students to cope with ESL/EFL writing: the teacher’s role

Of course, the teacher’s role and perspective is vital in taking students successfully though the process of becoming competent writers in ESL/EFL academic contexts. In my opinion, teacher knowledge of textual-generic (rhetorical) aspects of writing come first but an awareness of cognitive-psychological and intercultural distinctive features is crucial, too, for the instructor to play a significant part in coaching students effectively. These elements will allow the teacher to make the right predictions and arrive at an accurate diagnosis of the situation and the problems that need tackling.

In fact, this process has to be a conscious one for trainees, too, as far as possible, which cannot happen unless teachers are well aware themselves. Indeed, it is essential that both teacher and learner be made aware of differences in text organization and argumentation between their first language and their target language in the teaching of writing. Not only that, I believe it is also useful for both to be able to anticipate possible reactions and attitudes to Anglo-European rhetorics.

There is, on the other hand, a final consideration that could eventually enrich the debate, namely, where to tackle ‘problems’ and where not. To what extent should divergence be considered problematic, that is, a seemingly deviant feature worth putting right, without thwarting creativity or individual expression? It seems to me that there should always be room for the expression of individuality, the assertion of ideologies or in-group traits, including peculiar rhetorical manners, as long as these keep within certain loose-typicality boundaries. In fact, these are features that cut across different groups and communities, inside and outside culture-bound categories. In my view, there is some tension here between urging one’s students to comply with expected standards for the sake of comprehensibility and mutual understanding, and discouraging imagination and a welcome amount of risk-taking. All in all, this seems to be an issue that must be managed with insight and flexibility.

Conclusion

It has been fifty years now since CR first made its entry on to the academic scene. Some voices are still bent on a principled but narrow-minded dispute over its supposed Orientalism, but CR has been able to grow out of several objections raised against it and move on. A number of typical and non-typical features have been identified empirically and described in an extensive body of academic and professional genres (Connor, 1999, pp. 130-148). CR has also pinpointed specific discourse distinguishing features for different languages, mainly English and Romance languages, and hinted at the fact that such distinctive features are rooted in particular philosophical and epistemological traditions (Bennett & Muresan, 2016), which reveals a genuine willingness to understand Otherness in its dynamic complexity. With the contributions from Genre Analysis, it has gained in insight and scope and legitimised its place in the field of English for Academic Purposes. Not only that, it has become relevant for the teaching of writing even outside ESL/EFL settings.

Furthermore, the fact that CR attempts to outline the typical features of English academic discourse does not make it liable for charges of ‘Orientalism’. Indeed, the notion of typicality proves quite useful as a criterion for genre identification. Native speakers chart their understanding on such notions and there seems to be no reason why non-natives should not follow suit. In addition, pointing out certain distinctive style and organisation features does not by itself mean criticising or underestimating forms of argumentation that are not typically English. After all, the whole point of current intercultural rhetoric (IR), the updated version of CR, is to understand the scope of cultural differences and explain how they affect communication. Written intercultural encounters can shed light into the ways interactants negotiate their L2 educational, social and cultural backgrounds in writing and the reasons behind it. Greater cultural sensitivity will eventually lead to more effective communication.

Finally, experience suggests that while some non-native ESL/EFL undergraduates have a clear will to conform to English rhetoric, others gradually learn to accommodate to it as they feel part of the in-group. A few, though, are seen to refuse to give in to the rhetorical expectations of the foreign language or perhaps simply take longer doing it. Ultimately, this latter reaction could be pointing perhaps to a desire to make a cultural statement about their group belonging in similar ways as non-native speakers of English wish to retain some of their accent as a mark of cultural identity (Brown & Yule, 1983, p. 22). All things considered, though, it is worth remembering that deviating from the norm is often a way of legitimising it.

References

Bhatia, V. K. (1993). Analysing Genre–Language Use in Professional Settings. London: Applied Linguistics and Language Study Series.

Bhatia, V. K. (2004). Words of written discourse. A genre-based view. London: Continuum.

Bennett, K. & Muresan, L.-M. (2016). Rhetorical incompatibilities in academic writing: English versus the romance cultures. Synergy (12)1, pp. 95-119.

Berkenkotter & Huckin, T. N. (1993). Rethinking genre from a sociocognitive perspective. Written communication, 10(4), 475-509.

Brown, G. & Yule, G. (1983). Teaching the Spoken Language. An approach based on the analysis of conversational English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Connor, U. (1999). Contrastive rhetoric: Cross-cultural aspects of second language writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Connor, U. (2002). New directions in contrastive rhetoric. TESOL quarterly, 493-510.

Connor, U. (2008). Mapping multidimensional aspects of research: Reaching to intercultural rhetoric. In U. Connor, E. Nagelhout, & W. Rozycki (Eds.), Contrastive rhetoric: Reaching to intercultural rhetoric (pp. 299-315). Amsterdam Philadelphia: John Benjamins Pub.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977. New York: Pantheon Books.

Foucault, M. (1972). The archaeology of knowledge. New York: Pantheon Books.

Kaplan, R. B. (1966). Cultural thought patterns in inter-cultural education. Language learning, 16(1-2), 1-20.

Kaplan, R. B. (1988). Contrastive Rhetoric and Second Language Learning. Notes towards a Theory of Contrastive Rhetoric. In A. Purves (Ed.), Writing across Languages and Cultures: Issues in Contrastive Rhetoric (pp. 275-304). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Matsuda, P. K. & Atkinson, D. (2008). A conversation on Contrastive Rhetoric: Dwight Atkinson and Paul Kei Matsuda talk about issues, conceptualizations, and the future of contrastive rhetoric. In U. Connor, E. Nagelhout, & W. Rozycki (Eds.), Contrastive Rhetoric: reaching to intercultural rhetoric (pp. 277-298). Amsterdam Philadelphia: John Benjamins Pub.

Pennycook, A. (1999). The cultural politics of English as an international language. London New York: Routledge.

Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. New York: First Vintage Books.

Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[1]* Traductora Pública Nacional en Lengua Inglesa de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Maestranda en Lengua Inglesa por la Universidad de Belgrano. Profesora en Inglés del Instituto Superior de JN Terrero. Correo electrónico: amoldero@fahce.unlp.edu.ar / anamoldero@gmail.com

Ideas, V, 5 (2019), pp. 1-12

© Universidad del Salvador. Escuela de Lenguas Modernas. Instituto de Investigación en Lenguas Modernas. ISSN 2469-0899

[2]. The three modes of persuasion in classical rhetoric: logos, the propositional content of the argument in terms of logics and reasoning; ethos, the rhetor’s ethical character and fundamental values on which rests his credibility; pathos, the emotive nature of the rhetorical text, capable of stirring feelings in an audience.

[3]. The five canons of rhetoric first codified in classical Rome: invention, arrangement, style, memory and delivery.

[4]. The expression first appeared in John Dryden’s 1672 play The Conquest of Granada and has come to symbolise the uncorrupted nature of the indigenous other.

[5]. A late 18th century type of institutional building, designed by Jeremy Bentham, English philosopher and social theorist. The design is conceived so as to allow all (pan-) inmates in an institution to be watched (-opticon) by a single watchman without the inmates being able to tell whether or not they are being observed.

[6]. A neologism introduced by Foucault to explain the way he understands power. In his view, power is based on knowledge and uses knowledge to reproduce power. By the same token, power reproduces knowledge by shaping it in accordance with its anonymous intentions.

[7]. My own description of the process.